For both the characters and creators of Into the Woods, collaboration is key. After all, “No One is Alone.”

The collaboration between playwright James Lapine and lyricist/composer Stephen Sondheim seemed an unconventional one, given both were at different stages of their careers at the time and with different theatrical backgrounds. Lapine came from the Off-Broadway non-musical world while Sondheim was a Broadway musical veteran. However, finding common interest in the types of stories they wanted to tell, the two used their respective backgrounds to complement each other perfectly and created several classic musicals. The seeds of the Sondheim/Lapine collaboration began in 1982, when Sondheim saw Lapine’s play Twelve Dreams about a case study of Carl Jung’s.

Pictured: Stephen Sondheim.

Intrigued by Lapine’s blending of reality with fanciful imagination, Sondheim wanted to work with the younger writer. The sentiment proved mutual and their first collaboration was Sunday in the Park with George in 1984, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. After the success of their first collaboration, the two immediately set about finding another show to work on together. Sondheim suggested a musical in the vein of The Wizard of Oz. He loved the movie because the songs worked both to propel the story forward and as catchy stand-alone tunes of their own. However, Lapine worried that they would struggle to sustain a full-length fantasy story because, to borrow the very last line of Sunday in the Park with George, there were “so many possibilities.” In a fantasy story, anything is possible, so without a point to make the story could go absolutely anywhere. They had a genre they wanted to play with, but no content to drive it.

Lapine then suggested the idea of creating an original musical in the style of classic fairy tales, an idea they both loved although it came with a new set of obstacles. Fairy tales are always short, so creating a new one as a two hour plus musical would not feel authentic. Fairy tale adaptations, such as Disney movies, use the original tale as a springboard and are still typically less than two hours. But if one fairy tale wouldn’t be enough, why not adapt many? A year earlier, the two collaborators had come up with an idea for an ambitious crossover TV special: a bunch of characters from situational comedies would end up in a car accident, investigated by characters from cop shows, and treated in a hospital by characters from medical dramas. Lapine realized they could apply the concept to their musical. A bunch of characters from different fairy tales would go on a quest, with their lives and problems intertwining with each other.

Pictured: Gary Griffin‘s production of Into the Woods at The Muny (2015). Photo by Phil Hamer, Courtesy of The Muny.

And where would all of these fairy tale characters naturally journey together? Why, into the woods, of course! The woods has a certain duality to it in fairy tales; it’s a place of darkness and mystery, but also of reflection and knowledge. Characters face great peril and tribulations in the woods but emerge having gained wisdom and a greater sense of purpose. A setting like this could easily sustain a new original fairy tale. And yet, there was one more thing that bothered the writers: every fairy tale ends with characters solving their own problems and living happily ever after. Lapine found that every “happily ever after” came from little acts of dishonesty in their stories. Characters decided they had solved their problems and moved on with loose ends still left untied. In reality, these lies could have dire consequences, which would prevent a long-term happy ending. Jack may decide to live happily ever after killing a giant, but that doesn’t mean there are no more giants left. In order to eschew the false expectations of classic tales, Sondheim and Lapine decided to write one that would deal with life after happily ever after.

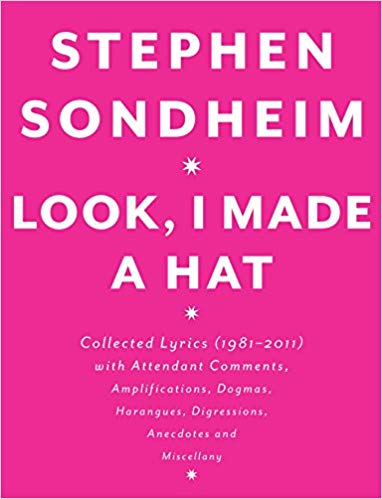

Look, I Made a Hat by Stephen Sondheim

The creators still felt the need to provide a gateway into the world of this show for people to connect to. While audiences may recognize the characters of Rapunzel and Cinderella, they likely wouldn’t relate to them. Few people have been locked in a tower for most of their lives or suddenly found themselves turned into royalty after attending a ball. To remedy this, Sondheim and Lapine created a Baker and his Wife that live in a fairy tale world but “are at heart a contemporary urban American couple,” as Sondheim writes in his book Look, I Made a Hat.

The other fairy tale characters may have royal pains or magical mishaps, but the Baker and his Wife simply want to start a family. Sondheim and Lapine used these two central characters as a starting point, and from there, they introduced all of the other fairy tale characters and their issues at hand. The first act is more of a traditional retelling of various fairy tales. Then in act two, the characters realize their desires had unintended consequences and understand that they all must work together to try to set things right. Still, the show had to have heart. Sondheim remarked that he found himself writing his most compassionate songs “to express the straightforward, unembarrassed goodness of James’s characters.”

Into the Woods first debuted at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego, California in 1986. During an early performance there, a women’s theater club started to leave after the first half, recognizing that the fairy tales had all reached their traditional conclusions. Luckily, they were notified just in time and, as Sondheim recalls, “returned and enjoyed the second act even more.” The team made sure to clarify that the show had two acts, and that while fairy tales may cut off after the characters are content, their lives don’t end there. The musical opened on Broadway in 1987. Directed by Lapine and starring Bernadette Peters, Joanna Gleason and Chip Zien, it won three Tony Awards. At one point during development of the musical, Stephen Sondheim predicted that, “if the piece worked, it would spawn innumerable productions for many years to come, since it dealt with world myths and fables.” Every year since its Broadway debut, several theater companies perform a version of the show, and like the many iterations and variations of the folk tales themselves, productions vary in tone, theme and subject. Because folktales are universal and withstand the test of time, the musical feels as timely and relevant as ever. Here at Writers Theatre, we welcome you into a world that is unique to us and our community. This is your Into the Woods.

Pictured: Gary Griffin‘s production of Into the Woods at The Muny (2015). Photo by Phil Hamer, Courtesy of The Muny.

No comments yet.