Only three performances of A Moon for the Misbegotten remain! Don’t miss this production!

What is American Theatre?

Images of the great works of Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller and August Wilson may cross your mind. These playwrights, while equally ferocious writers, built very different constructs of America. Often writers like O’Neill, Williams, and Miller wrote family plays depicting white working class families attempting to achieve the American dream. African-Americans were consistently erased from these narratives, despite the face that they were living similar lives. While the famous faces associated with the plays of all but August Wilson tend to be white, it is fact that people of color lived through many of the same economic developments and difficulties as white citizens in America at the same time.

A notable product of The Great Migration was Greenwood, Oklahoma, a neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma affectionately called “Black Wall Street.”

Reconstruction, an effort from President Lincoln to reinvigorate the South economically and build new opportunities for freed black people after the Civil War, was a miserable failure that led to violence and poverty. Hundreds of thousands of African-Americans left the South from 1916-1970 in an exodus that historians call The Great Migration. One child of The Great Migration is the famous actor James Earl Jones who migrated north from Mississippi in the 1920s at the age of 4 with his family. A notable product of The Great Migration was Greenwood, Oklahoma, a neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma affectionately called “Black Wall Street” for its prosperity in business. Home to some of the greatest black physicians of the time, Greenwood thrived until 1921, when it was the victim of one of the worst race riots in history. Hundreds were murdered and the area was burned to the ground, leaving 10,000 homeless. Prior to its demise, Greenwood, Oklahoma could have been the home of the Lomans in Death of a Salesman. Greenwood represents an entire generation of African-Americans who were determined to work their way up in the world and get their piece of the American dream. Many do not even know of the existence of Greenwood because of its erasure, but the experiences of those working class and middle class African-Americans is just as much in the fabric of our nation as Willy Loman’s “universal” experience.

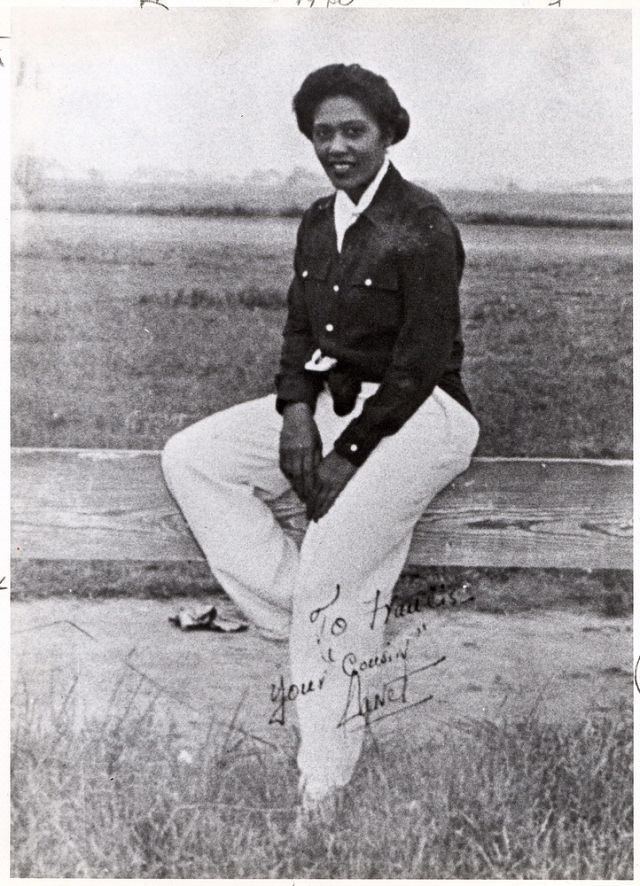

Janet Harmon Bragg earned the first commercial pilot’s license ever issued to a black woman in 1934. Black fliers were not allowed to fly out of airports used by whites. The solution: she, her classmates and her instructors formed the Challenger Aero Club, purchased land in the all-black town of Robbins, Illinois and built their own airfield. Photo courtesy of Hill Air Force Base.

If you are a tried-and-true theatre fan, you may be familiar with the following August Wilson quote from a 1996 address: “To mount an all-black production of a Death of a Salesman or any other play conceived for white actors as an investigation of the human condition through the specifics of white culture is to deny us our own humanity, our own history, and the need to make our own investigations from the cultural ground on which we stand as black Americans.”

I firmly believe that Wilson is correct–when a play with a culturally white context is simply put onto black bodies with no thought process, the outcome can be disastrous. There are countless examples of color-blind casting in plays that create a more marginalized picture than if they had erased people of color from the plot entirely. The choice for Writers Theatre to depict the Hogan family as African-American in this production of A Moon for the Misbegotten did not arise out of a gimmick, but rather a desire by director William Brown to show a different, and yet more familiar reality. After reflecting on the America he knew and had grown up in, Brown came to the conclusion that it made sense to fill this story with the lives of people he had lived alongside and interacted with – working class African-American families – rather than the lives of Irish immigrants at which he could only guess. This choice is key in discovering details about our American history we don’t often get the choice to investigate, especially in historically white institutions.

In most productions of A Moon for the Misbegotten, the Hogan family is dressed simply, often with worn out clothes or some other indication of being low-income.

The specificity of this process has included conversations about how a working class African-American family would have truly lived in the 1920s. Connecticut saw an influx of African-Americans between 1915 and 1930. 40% of school enrollments in 1925 Hartford, Connecticut were African-American students, and Hartford’s NAACP chapter was granted their charter on December 10th, 1917. At the turn of the 19th century, one-fifth of African-Americans in the United States owned their own homes, and half of black men and thirty five percent of black women who reported an occupation to the census bureau worked as a farmer–just like Phil, Josie and Mike Hogan.

Courtesy of St. Augustine Historical Society.

Another topic to consider is fashion. In most productions of A Moon for the Misbegotten, the Hogan family is dressed simply, often with worn out clothes or some other indication of being low-income. An early discussion about costumes for this production was about what the African-American working class looks like. Most families I personally know believe that if you are poor or low-income, there is no reason that you should look like it. Oftentimes folks from modern day working-class Black families are generally wearing well-mended, fashionable and cared for clothing. Especially back in the day, Black folks typically dressed with care, and the surviving images we find reinforce that concept.

Circling back to Wilson’s quote above, it is absolutely necessary for African-American artists to interrogate a history that has been hidden from them. It is my personal belief that we must also search for ourselves in the experiences from which we have been erased, that we shared with the rest of America, and weave ourselves back into this Nation’s history. It is especially important when we consider young people attending our shows and seeing all-white casts of families from the 40’s and 50’s. Will they subconsciously understand that people of color must be somewhere inside the narrative? Or will they leave the theatre believing that they did not exist in the same capacities or arenas as white citizens at that time?

In this production, there is an attempt to universalize through specificity. The Hogans are the same O’Neill family American Theatre has grown to love, but the specificity of their dilemmas in this production highlight them and American history in a hopefully exhilarating and challenging way.

No comments yet.