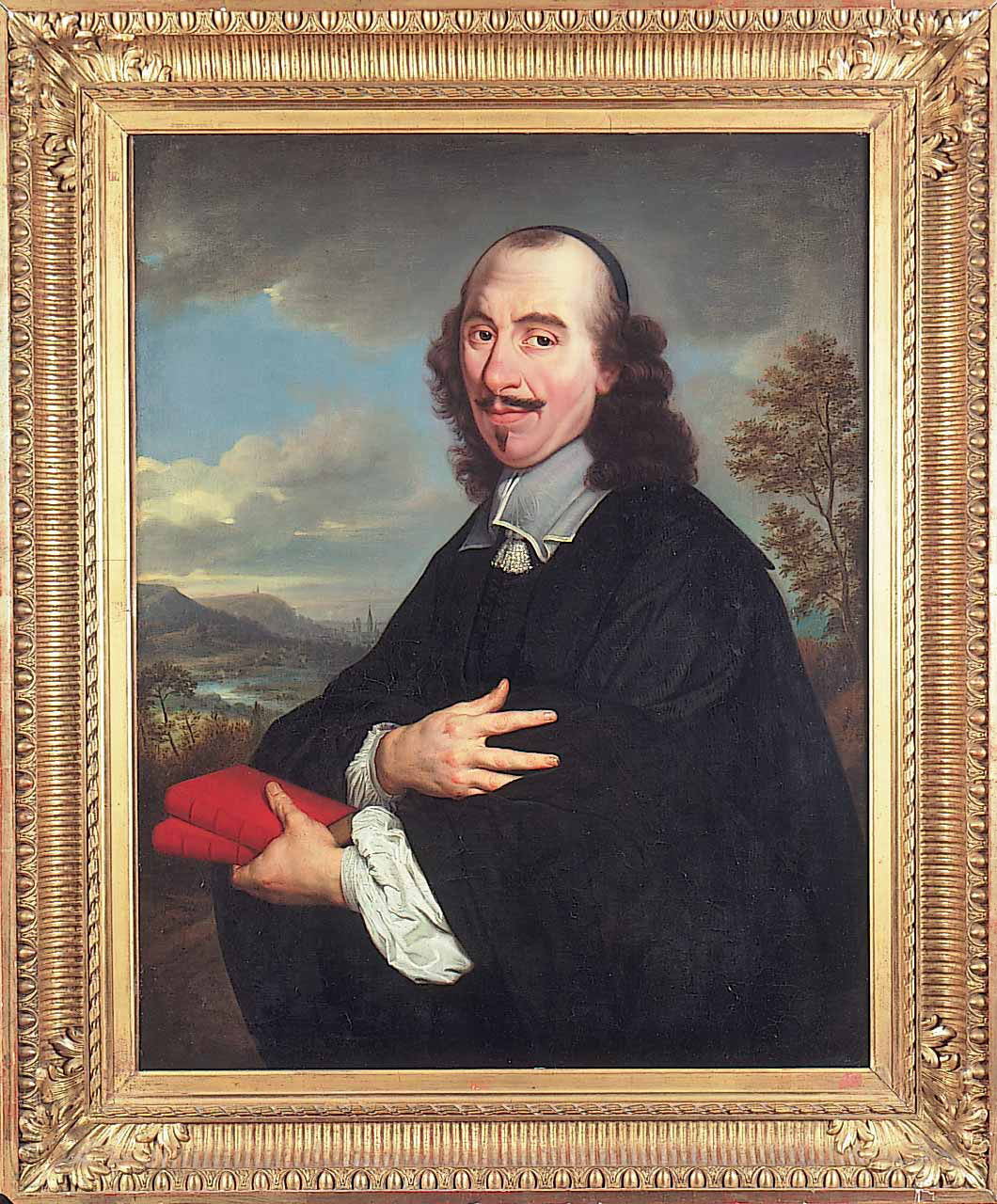

Pierre Corneille, while lesser known than his younger contemporaries Molière and Racine, had just as great an impact on the development of classical French drama.

In the 17th century, the French theatre had yet to truly flourish the way the English and Spanish theatres had. Corneille was the first major dramatist to emerge in what would become a great tradition of French theatre. Although he is most lauded by scholars and historians for revolutionizing tragedy, the playwright’s comedies were equally impressive and groundbreaking.

Born in Rouen in 1606, Corneille wrote his first play, a comedy entitled Mélite, before the age of twenty. The play made it to Paris in 1630 and became a surprise success, prompting the author to move to the city, where he wrote a number of successful comedies over the next few years (including 1636’s L’Illusion comique, later adapted by Tony Kushner into The Illusion). His nearly instant fame attracted the attention of Cardinal Richelieu, who invited Corneille to join a group of writers he was assembling called les cinq auteurs (“the society of the five authors”), but personality clashes led to Corneille departing to return to Rouen.

At this time, the rules of what constituted a classical tragedy were being rewritten. Interpreting the theories put down in Aristotle’s Poetics, French scholars decided that all tragedies needed to observe the classical unities of time (a play should take place between sunrise and sunset), place (one location), and action (subplots should be avoided).

Corneille’s first true foray into tragedy was Le Cid, first performed in 1637. The play was a groundbreaking step for French tragedy, however despite its popularity, public performances were suppressed because it did not strictly adhere to the classical unities. After a wound-licking hiatus of three years, Corneille returned to the theatre with three more classical tragedies—Horace (1640), Cinna (1641), and Polyeucte (1643)—which along with Le Cid embody Corneille’s “classical tetralogy.” All of these works feature a central moral dilemma that consumes the protagonists’ attentions and a moment of truth in which they realize the extremity of their involvement in the unfolding situation.

Corneille continued to write mostly tragedies over the next few years, but during the same time frame he also penned The Liar (Le Menteur) in 1643, his first comedy in seven years. Borrowing the plot from a Spanish adventure story, Corneille turned the piece into a comedy of manners featuring intricate wordplay. The play built upon the popularity of commedia dell’arte in France during the early Renaissance, successfully taking inspiration from the stock characters and narrative devices of commedia and appropriating them into a scripted drama.

Corneille continued to write mostly tragedies over the next few years, but during the same time frame he also penned The Liar (Le Menteur) in 1643, his first comedy in seven years. Borrowing the plot from a Spanish adventure story, Corneille turned the piece into a comedy of manners featuring intricate wordplay. The play built upon the popularity of commedia dell’arte in France during the early Renaissance, successfully taking inspiration from the stock characters and narrative devices of commedia and appropriating them into a scripted drama.

The Liar was so successful that Corneille wrote a sequel (aptly titled La Suite du Menteur or Sequel to the Liar) in 1645. The success of the original also proved an enormous influence on a young man who would eventually become the master of French comedy, Molière. “I am much indebted to Le Menteur,” he confessed. “When it was first performed, I had already a wish to write, but it was in doubt as to what it should be. My ideas were still confused, but this piece determined them.” Molière’s theatre company performed a number of Corneille’s plays, both comedies and tragedies, upon settling in Paris, and the two collaborated on a play, Psyché, in 1671.

The rest of Corneille’s career was marked with periods of prolific output alternating with years of inactivity. From 1659 to 1673, he wrote almost one play a year, after having not written a single play for eight years prior to that. He wrote Tite et Bérénice to deliberately challenge Racine’s Bérénice, but Cornellie’s version proved less popular than the younger playwright’s piece, indicating the direction of French drama had shifted. Racine would go on to build upon Corneille’s innovation and perfect the art of pure tragedy in masterpieces like Phèdre.

At the time of Corneille’s death in 1684, the playwright’s lasting influence and recognition seemed unquestionable. Despite the censorship of Le Cid, the public held Corneille in great esteem, as did the scholars of the time. It wasn’t until the mid- 18th century when the philosopher Voltaire published a mostly scathing critique of the playwright that Corneille’s reputation began to diminish, while Racine and Molière remained canonized. Only recently has that trend reversed, as scholars now fully acknowledge Corneille’s immense contributions to the renowned French dramatic tradition.

No comments yet.