A lot has changed in 150 years.

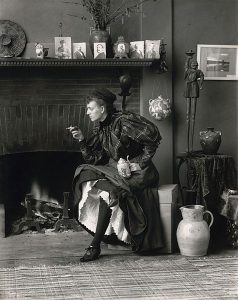

Pictured: New Woman, self-portrait by Frances Benjamin (1896). Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

When Ibsen was writing A Doll’s House, Norway was united in a kingdom with Sweden, having been forced into the union in 1814 during the Napoleonic wars as a punishment to Denmark, with whom Norway had previously been united since 1397. Although the country’s economy had started to industrialize and modernize, Norway was a secondary province of a larger empire and therefore its capital, Oslo (named Christiania until 1925), was always a step further removed from the center of European culture and trade than Copenhagen and Stockholm. Having achieved its independence via referendum in 1905, Norway prospered in the second half of the 20th century due in large part to the discovery of oil in the North Sea. As a result of its location on the fringes of Europe, however, Norway has never fully integrated with the continent, remaining outside the European Union and still using its own currency, the Norwegian krone.

Given Norway’s geographical isolation and its never having been a colonial power or part of the transatlantic slave trade, there had never been a major influx of immigrants to the country prior to the 20th century. The Sami people, indigenous to the northern regions of Scandinavia, have been the only significant minority population for much of Norway’s history. In the 1960s, the population began to diversify and today the country of over 5 million is only 84% Norwegian. Half of the non-native population comes from other areas in Europe, while the other half comes from outside the continent.

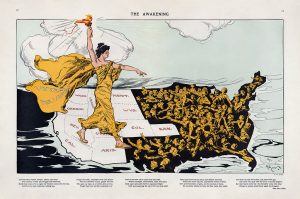

Pictured: The Awakening by Henry “Hy” Mayer (1915). Lady Liberty, wearing a cape labeled “Votes for Women,” stands astride the states (colored white) that had adopted suffrage. A poem by Alice Duer Miller is printed beneath. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

Norway also did not have as established and influential an aristocracy as most of Europe. This was due to first being decimated by the plague and then being subservient to Denmark and Sweden. As a result, women had been part of the workforce with much more regularity and less stigma than elsewhere in Europe and around the world. Single women (predominantly widows, spinsters and women age 18-25) were officially given the right to work in certain trades as early as the 1830s. This was followed by inheritance rights and full legal capacity in the 1850s and 1860s. Marriage and motherhood was still the preferred societal route for a woman, however, and so married women were not given these same rights.

At the time Ibsen was writing, a movement for more equal treatment for all women was gaining steam. The Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights was established in 1884, around the same time women were permitted at universities. Married women were finally given full legal capacity and the right to manage their own earnings in 1888. After universal suffrage was extended to all men regardless of status in 1898, there was a growing fear of lower-class men voting for socialist candidates and policies. In response, the government extended the right to vote to women with a significant personal income in 1901, calculating they would vote more conservatively and balance out the radicals. Universal women’s suffrage was finally passed in 1913, making Norway one of the first countries in Europe to achieve the milestone. While a gender gap still persists today, Norway scores near the top on gender equality studies, while marriage and birth rates are at all-time lows.

Pictured: The Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights first board (1904). From left: Karen Grude Koht, Fredrikke Marie Qvam, Gina Krog, Betzy Kjelsberg and Katti Anker Møller. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

Although Norway may seem an unlikely comparison, the United States has had a similar trajectory in most of these areas. In the 1870s, the US was also remote and not at the center of the Western world. The country was still recovering from the Civil War and the failed efforts of Reconstruction that followed. In the post-war era, the United States also enjoyed remarkable economic prosperity, albeit not as evenly distributed as in Scandinavia. Meanwhile, the country has gone from being 87% non-Hispanic white in 1900 to only 64% non-Hispanic white today. According to current projections, the country will become majority-minority (meaning non-Hispanic whites will make up less than 50% of the population) in 2045. Progress on women’s rights was slower and more fragmented in the United States than it was in Norway, with some states passing their own laws on the subject ahead of others. When the 15th amendment was adopted in 1870, it notably did not add “sex” to the list of reasons one can’t be denied the right to vote, spurring on the suffragette movement. After fifty years of activism, the 19th amendment was finally passed in 1920, extending the right to vote to women on a national level.

Given that early conversations about women’s suffrage were the backdrop for Ibsen’s writing of A Doll’s House, seeing his play performed while in the midst of the generation-defining #MeToo movement provides another link between Nora’s world and our own.

No comments yet.