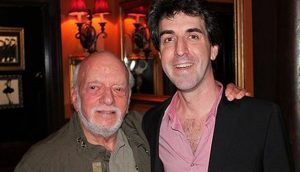

Pictured: Alfred Uhry

Pictured: Jason Robert Brown

Alfred Uhry was born in Atlanta, Georgia to a Jewish middle class family. After graduating from Brown University, he moved to New York to pursue a career as a bookwriter and lyricist for musical theatre. An early supporter of his was the composer Frank Loesser (Guys & Dolls) who employed Uhry at his publishing company for several years. The writer worked on several musicals at the beginning of his career, some more successful than others, but the work wasn’t satisfying enough creatively or financially. Uhry related this in an interview with Thomas Cott in 1999, saying, “I was shaving. And most guys, when you shave, you don’t really look at yourself, you just kind of do it. But all of a sudden I looked at myself in the mirror, with my face full of soap, and I said, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore.’ […] I had four kids, and I was trying to make a living of some sort. And I was teaching school part-time, and I thought, ‘Well, I’ll just go teach school full-time.’ But meantime, I had an idea—I had never written a play, but I had an idea for a play, a little bitty play about my grandmother and her chauffeur, and I wrote it, and my life changed.”

‘I wonder why those Atlanta Jews were so desperately assimilating?’ And I said, ‘Well, probably because of Leo Frank.’

That “little bitty play” was Driving Miss Daisy, which premiered at Playwrights Horizons in New York in 1987 and ran for three years, winning a Pulitzer Prize for Drama along the way. The show also made a star out of Morgan Freeman, who reprised his role in the 1989 film alongside Jessica Tandy and Dan Aykroyd. All three performers were nominated for Oscars, with Tandy winning. Uhry won an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay as well. The playwright had another success with his next play, The Last Night of Ballyhoo, which premiered in 1996 at the Olympic Arts Festival in Atlanta during the Summer Olympics, moving to Broadway in 1997 and winning a Tony Award for Best Play.

Following this considerable success, Uhry was talking to legendary producer/director Hal Prince about working on a musical again after years away from the genre. As Uhry described it to Cott, “I was talking to [Prince] about Ballyhoo. And he said, ‘I wonder why those Atlanta Jews were so desperately assimilating?’ And I said, ‘Well, probably because of Leo Frank.’ He said, ‘Tell me the story.’ And I did. And he jumped up out of his chair, literally, […] and he said, ‘This is the musical I have been looking for. This is the musical I want to do.’”

Prince had recently come to know a young composer, Jason Robert Brown, who was primed for a breakthrough success. In 1995, Brown debuted with a show called Songs for a New World, which was a collection of songs he had written while working as a pianist and music director on other composers’ shows. Brown talked about the work in another interview Cott conducted in 1999, explaining “It was stuff that I had written for shows that I had never finished because they were terrible ideas. […] And then I also started writing other songs that I just thought would be fun. I was working at piano bars and thought, ‘Oh this would be good for this singer to do.’ And somehow the songs just all started making sense together, with kind of an emotional narrative to the whole piece.” Songs for a New World was directed by Daisy Prince, Hal’s daughter, which got him introduced to the producer/director. After working as a pianist and then music director on some projects of Prince’s, Brown was invited to a meeting with Alfred Uhry to talk about what would become the musical Parade.

‘Because I’m Southern, and I know that those people suffered. I know that they were defeated. I know that their lives were ruined, and they had believed in that cause with all their heart and soul, and that they lost.’

Uhry and Prince told Brown the story of Leo Frank and their vision for the musical, after which Brown went away and wrote a song as an audition (“a bad song” as Brown described it). However, the second song he wrote, after months of further discussions, was “The Old Red Hills of Home,” the musical’s opening number. Uhry remembered “I really was moved to tears by it, and still am. I told [Brown] when I started this, that I didn’t want this to be some sort of noble thing about this Jewish man who was brought down by vicious rednecks, because I didn’t see it that way. Because I’m Southern, and I know that those people suffered. I know that they were defeated. I know that their lives were ruined, and they had believed in that cause with all their heart and soul, and that they lost. And not only did they lose, they went home, they lost their farms. They had been moved to town, and they had to put their little kids to work. It was a hard thing. And I told him some things about the South, he read some things about the South, and then he wrote that amazing song. And I called Hal and said ‘Sign him.’”

Pictured: Harold Prince and Jason Robert Brown

After several years of readings and workshops, Parade premiered on Broadway at Lincoln Center Theater’s Vivian Beaumont Theatre in December 1998 and ran until February before closing. However, several months later both authors won Tony Awards for their work, taking home Best Book and Best Score. In response, a national tour was organized in 2000 that went to seven major American cities. Chicago was intended to be a stop, but the engagement was cancelled after the downtown venue at which the tour was booked changed ownership. Although there have been several non-Equity productions at storefront Chicago theaters, WT’s production will be the first local production by an Equity theatre company.

In the years after Parade debuted, Brown would continue to compose highly regarded and successful musicals, including The Last Five Years (2001), 13 (2007), The Bridges of Madison County (2013) and Honeymoon in Vegas (2013). He won a second Tony Award, also for Best Score, in 2014 for Madison County. Uhry continued to work on both plays and musicals. He collaborated again with Hal Prince on LoveMusik in 2007 (earning a Tony nomination for Best Book) and again with Brown on My Paris in 2015.

Nine years after it premiered in New York, a major remount of Parade was produced at London’s Donmar Warehouse under the direction of Rob Ashford, who engaged Uhry and Brown to revisit the musical. The show was condensed from a cast and orchestra of more than 60 down to 15 actors and 9 musicians. Brown and Uhry reworked sections of the script and even introduced some new songs. The production was a hit and received several Olivier Award nominations. The Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles brought the revised version over to the U.S. in 2009, and the musical has been widely produced around the country ever since.

When Griffin first saw the Alexandra C. and John D. Nichols Theatre at Writers Theatre during the company’s Grand Opening festivities, he knew that this was the place.

The enduring love for Parade led to a one night concert staging at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall in February 2015, the first professional showing of the musical in New York since its debut in 1999. Brown directed the 28-piece orchestra himself, and the concert staging was directed by Chicago’s own Gary Griffin. Griffin had previously directed the world premieres of two other Brown musicals, Trumpet of the Swan and Honeymoon in Vegas. Following the success and acclaim of the one-night concert, Griffin and the authors began to discuss mounting a full production of Parade that Gary would direct with the authors’ continued consultation. When Griffin first saw the Alexandra C. and John D. Nichols Theatre at Writers Theatre during the company’s Grand Opening festivities, he knew that this was the place.

These many years since its original production, the writers are thrilled to see that the musical still has a life and that audiences are still moved by it. “I don’t spend a whole lot of time thinking, ‘Gee, it should have run a lot longer on Broadway,’” said Brown to Playbill the day before the 2015 concert. “I mean, it was a musical about a terrible, terrible event. It is a very sad piece of work, so I don’t know that it needed to be The Book of Mormon—that’s not what it was, but we got to tell it, and we’re still getting to tell it, and that means everything in the world to me.”

No comments yet.