“Oh! Sorry, my apologies. Can’t believe it slipped my mind. I’m the devil.” –Witch

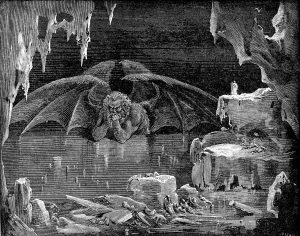

Pictured above: Gustave Doré’s engravings illustrated the Divine Comedy (1861–1868); depicted here, Lucifer, King of Hell. Via Wikipedia Commons.

Every culture and religion has had to consider the nature and origin of evil. If some sort of intelligence created the universe, are they then also responsible for evil? Most societies conclude that the intelligence that created the universe is ambivalent, that it embodies both good and evil, causing both to happen in the world. Only four major religions have created what scholar Jeffrey Burton Russell calls “a single personification of evil[:] Mazdaism (Zoroasrianism), ancient Hebrew religion (but not modern Judaism), Christianity, and Islam.”

The attempt to understand evil’s place in the world occupied much of early Hebrew and Christian theology. As the Hebrews began to conceive of God as “all-powerful and all-good” (as opposed to ambivalent, like other religions), they began “to posit as the source of evil a spiritual being opposed to the Lord God,” Russell writes in his book, The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History. “The Hebrews’ insistence upon God’s omnipotence and sovereignty did not allow them to believe that this opposing principle was independent of God, yet their insistence on God’s goodness no longer permitted it to be part of God. It had therefore to be a spirit that was both opposed and subject to God.”

Satan is a Hebrew word that “derives from a root meaning ‘oppose,’ ‘obstruct,’ or ‘accuse,’” explains Russell. Early Old Testament books such as Numbers and 2 Samuel use the word as a common noun. It’s not until later books such as Job and Zechariah that Satan is used to refer to a specific personality. Still, even in these books, Satan is seen as a tool or partner of God’s, carrying out his will or at least under his instructions. Between 200 B.C.E. and 100 C.E., the pseudepigrapha (Jewish books that were never included in the Old Testament at any point) advanced Satan’s agency, trying to make him as fully responsible for evil as a monotheistic religion could. While Rabbinic Judaism would ultimately reject the pseudepigrapha understanding of Satan after 70 B.C.E., early Christian theology built off these advances.

The New Testament, written in a much shorter amount of time than the Old Testament, had a more consistent view of the Devil. “The Devil is a creature of God, a fallen angel, but as chief of fallen angels and of all evil powers he often acts almost as an opposite principle to God,” writes Russell. “Satan is not only the Lord’s chief opponent; he is the prince of all opposition to the Lord. Anyone who does not follow the Lord is under Satan’s power.” Later, Christian theologians including St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, among others, would better explain the existence of evil in a divine universe, articulating that God gave humans free will so that we might choose good of our own volition. Without the freedom to choose, there could be no good for it would be compelled. It is only by being given the choice of evil that goodness can affirm itself and have value. Without vice there can be no virtue. This development of thought, which placed the blame for original sin more on Adam and Eve than ever before, marginalized Satan’s role in Christian theology.

At the same time, however, the Evil One was becoming a cultural fascination. Many of the characteristics and practices commonly associated with Satan come from folklore, not theology. His association with animals and his bestial appearance was due to the pagan gods’ fondness of other creatures. Folklore also propagated the idea that the devil could be outwitted in certain contests, such as wrestling, gambling and debate. The concept of a pact between the devil and a human would quickly transcend its populist origin and influence official church doctrine. As literacy among the general population grew, the presence of the Devil in literature and art flourished. While only briefly seen at the end of Inferno, Satan is a memorable presence in Dante’s The Divine Comedy, which was completed in 1320. He also appeared in many plays of the later Middle Ages, where the chronology of the angel’s creation to his fall were explored to the fullest extent yet and established the figure’s backstory that we commonly know today.

Also fueling the cultural popularity of Satan was a growing belief in rampant diabolical witchcraft. People began to be accused by their neighbors, friends and family members of having been corrupted by the devil and were now bewitching the innocent, flying on broomsticks and causing other mischief. The witch-craze, peaking between the 15th century and the 17th century, was responsible for the execution of tens of thousands of people both in Europe and in North America. The Witch of Edmonton appeared in 1621, towards the end of the witch-craze in Europe but still seventy years before the events in Salem, Massachusetts. The play shows how some people in London were starting to doubt that the people being accused were actually witches and that perhaps a tragedy of injustice was being perpetrated.

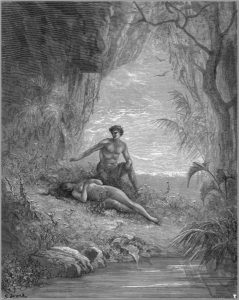

Pictured: Adam and Eve depicted in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Gustave Doré, 1866. Via Wikipedia Commons.

The first literary depictions of the Devil with at least serious complexity if not sympathy emerged at the same time as the witch-craze. A German legend about a man named Faust first appeared in print in 1587. A successful man but dissatisfied with his life, Faust makes a pact with Mephistopheles (as the Devil is called here), selling his soul in exchange for knowledge and power. After 24 years, Mephistopheles comes to collect and carries Faust off to Hell. Unlike Medieval stories, where the Devil was in conflict with God or Christ, here it is a human facing off with the Devil, alone, with no support from the Church. The story’s pessimistic ending was also groundbreaking, as are the glimpses of introspection and humanity in Mephistopheles. British playwright Christopher Marlowe would use the Faust legend to write his 1588 play The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus, which follows the German story closely, preserving the dark ending. It wouldn’t be until Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s version of the Faust story—Part One appearing in 1806, followed by Part Two in 1832—that the protagonist would be saved at the end.

John Milton’s Paradise Lost, an epic poem first published in 1667, is the most famous depiction of Satan as protagonist and influenced all subsequent characterizations of the Devil. The poem tells the story of the Fall of Man, as a result of Satan’s temptation of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, and includes references to how Satan was cast out of heaven. Whether or not Milton intended for it to be taken as such, Paradise Lost is cited as one of the first sympathetic portrayals of Satan, with some even calling his role in the epic that of an anti- or tragic hero. A subsequent poem, Paradise Regained, published in 1671, continues Satan’s story, covering his effort to tempt Christ in the Judaean desert.

As the 18th century ushered in the Enlightenment and science and reason pushed the world towards a more secular point of view, the presence of the Devil in serious art and literature diminished. Although he is called a “devil” and a “demon,” the monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was created by humans and taught evil by us (he also reads a copy of Paradise Lost). And in all the horror stories written by Edgar Allen Poe, the Devil is not a part of the darkest and most disturbing ones, only the ones with a more comedic and whimsical tone.

Pictured: C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. Via Flickr.

Although increasingly secular, writers of the 20th and 21st centuries continue to find creative inspiration in the idea of the Devil and a personification of evil. All of the historical representations and behaviors of Satan continue to be explored, whether it be demonic possession (The Exorcist), the creation of the Antichrist (Rosemary’s Baby), corruption of souls (C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters), or general causation of mischief and despair (“Sympathy for the Devil” by The Rolling Stones). On stage, the Devil has enjoyed an equally rich life. On the lighter end of the spectrum is the 1955 musical Damn Yankees, with its Devil-in-disguise character Mr. Applegate offering real estate agent Joe Boyd an opportunity to be a baseball star. A darker and more contemplative example is Irish playwright Conor McPherson’s 2006 play, The Seafarer, which portrays a rematch between the Devil and a man he lost a poker game to twenty-five years ago. With Witch, Jen Silverman adds another interesting chapter to the life of the Devil in art. Here we see the Evil One depicted as a junior salesman, eager to collect souls on his trip through Edmonton. Already quite skilled at his job, Scratch (as he is called in the play) has an unexpected and life-changing encounter with Elizabeth, the so-called Witch of Edmonton. After revealing more of his inner life than ever before, it is remarkably the Devil who is left searching his soul in order to make an all-important decision. Thousands of years after his debut, this fascinating figure continues to capture the imagination of artists and audiences alike.

Pictured: Ryan Hallahan and Steve Haggard. Photo by Michael Brosilow.

No comments yet.