In the early 1830s, a young boy stood atop a bell tower in Skien, Norway, and looked down.

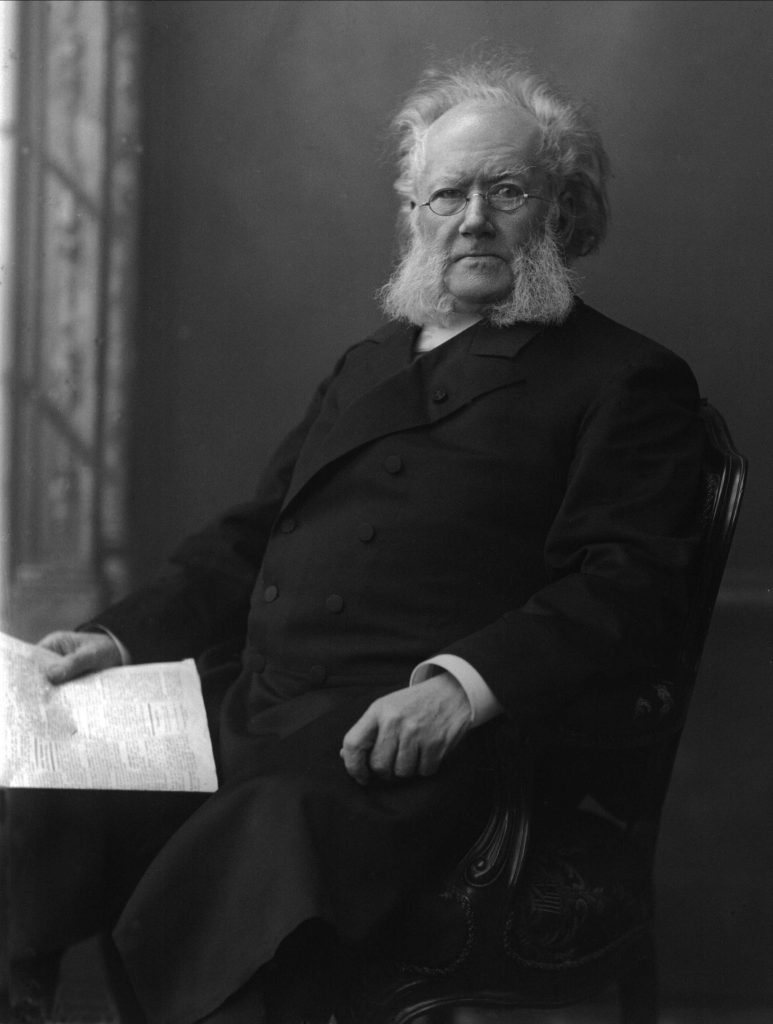

Pictured: Henrik Ibsen. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

From his vantage point, he could see the tiny hats of townspeople bustling to and fro, schoolboys throwing rocks and even his own mother hanging laundry. This, Henrik Ibsen later claimed, was the start of his career as a writer. “To write, that is mainly a matter of seeing,”[1] he explained. In that tower, he enjoyed the privilege of quietly watching, and the world he saw was brimming with stories. He saw his father, once a successful merchant, fall into financial ruin. He saw the business sold and the family moved into a small cottage outside of Skien. He saw the tensions of poverty take their toll on his mother, an artist and theatre-lover in her own right. He saw the workforce far too early, quitting school at fifteen to help support his family. He saw the comforts of his infancy fall away, taken over by hunger and the constantly counted coin. What he couldn’t see was that these observations would later turn him into one of the most influential playwrights of all time.

Pictured: Suzannah Ibsen, wife of playwright Henrik Ibsen, taken in Frascati, Italy. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

At 22, Ibsen moved to Christiania (now Oslo) and attempted to turn his observations into poetry. His eloquence and revolutionary spirit were noticed by violinist Ole Bull, who invited Ibsen to join the new National Theatre Company in Bergen as its dramatic author. This was a huge step for the burgeoning writer, but initiated fourteen years of struggle during which he wrote and failed and wrote and failed. One high point of this period was his marriage to Suzannah. An actress, mother to their son and an understated but brilliant thinker, Suzannah was a constant influence in Ibsen’s writing, and they lived very happily together, though in frequent poverty. By 1864, Ibsen had had enough of Norway, so they packed up and headed to Rome.

The move must have done him some good, for it was in Italy that he found how to voice his observations, saying “suddenly there dawned on me a strong and clear form for what I had to say.”[2] He began to write more plays. His early works, most famously Brand and Peer Gynt, were five-act epics, with strong verse, huge themes, and settings reminiscent of the avant-garde. They focused primarily on Norwegian folklore or other historical genres and made Ibsen a household name within Norway. Brand established his relationship with the prestigious Gyldendal publishing company, which was maintained until Ibsen’s death, and to this day Peer Gynt is one of his most produced plays. Peer Gynt also inspired a set of orchestral suites by Edvard Grieg that were extremely popular in Scandinavia and have retained their fame in pop culture through film and television. Thus, for the first time in his life, Ibsen was financially comfortable. But he wasn’t satisfied. In 1877, he made a drastic shift, writing intimate plays that were more focused on contemporary life than on grand themes of humanity. The first of these was The Pillars of Society, but Ibsen really hit his stride two years later with A Doll’s House.

American Theatre Magazine has called A Doll’s House a “proto-feminist classic.”[3] While that may be true, it wasn’t really ahead of the times. Ibsen saw the women’s liberation movement taking off. He saw the Danish Women’s Society and the Swedish Society for Married Women’s Property Rights founded in the early 1870s. He fought for women’s rights at the Scandinavian Society in Rome and saw outrage at his suggestion. Put simply, Ibsen wrote a feminist classic because he saw feminism in the people he watched. Still, these observations were revolutionary to his audience.

Pictured: From a 1936 edition of the play Peer Gynt by Henrik Ibsen, illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

Most people read A Doll’s House before they saw it. The first edition was published on December 4, 1879 to the tune of 8,000 copies. Within the month it had sold out, and two more editions soon followed, an unprecedented amount at the time. It was the talk of Europe, sparking debates, praise and outbursts in both the dining room and the public sphere. At the stage premiere three weeks after publication, audiences flocked to the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen with an opinion already in mind. The public was divided. J.P. Jacobsen wrote, “A Doll’s House seems to me decidedly the most important and successful thing Ibsen has ever done,”[4] while Ibsen’s peer and rival, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson said, “It is technically excellent but written by a vulgar and evil mind.”[5] Indeed, many spoke out about its moral failings. They worried that it would teach women to leave their families, and one newspaper even reported that “Eighteen married men of the town have handed in a petition to the board of the theatre demanding that no theatre company with A Doll’s House in its repertoire be allowed to perform in Växjö.”[6]

Even still, the play was considered by most to be a momentous achievement. Despite the initial explosion of success through print and productions in Norway, Denmark and Germany, A Doll’s House entered the international stage much more slowly. This was due in large part to the play’s ending; many countries refused to stage it as written. Thus, quite a few bastardized versions appeared internationally, and Ibsen even wrote his own alternate “happy ending” to try and appease an obstinate German actress. Surprisingly, audiences were not happy with the change, and these versions were often mocked. Finally, a faithful translation was produced in London in the late 1880s, Broadway saw a premiere in 1889, and France produced it in 1894. Since then, it has been translated, adapted, and performed all across the globe. There are at least eleven film versions, and Nora has become one of the most desirable roles for an actress. Through this international renown, Ibsen became known as the “Father of Modern Drama.” His contemporary life plays, with their close attention to inner psychology and fully human stories, have influenced playwrights ranging from Oscar Wilde to Arthur Miller to Suzan-Lori Parks. Such influence has prompted literary theorist Toril Moi to consider him “the most important playwright writing after Shakespeare.”[7] And it all began with what he saw.

Pictured: The central hall in the Gyldendal house in Oslo. Gyldendal Norsk Forlag is a publishing house in Oslo. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

[1] Ivo De Figueiredo, Henrik Ibsen (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 3.

[2] Thomas Van Laan, “Life and Works”, Ibsen Society, http://ibsensociety.org/ibsen-life-andworks/.

[3] Misha Berson, “Ibsen, Our Contemporary”, https://www.americantheatre.org/2018/03/26/ibsen-our-contemporary/.

[4] Michael Meyer, Ibsen, a biography (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971), 457.

[5] Ibid.

[6] De Figueiredo, 407.

[7] Toril Moi, Henrik Ibsen and the Birth of Modernism, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 48.

No comments yet.