By Bobby Kennedy, Literary Manager

![Pictured: The Ursa Major constellation from Uranographia by Johannes Hevelius. Photo by Torsten Bronger [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.writerstheatre.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/Ursa_Major_constellation_Hevelius.jpg)

- Pictured: The Ursa Major constellation from Uranographia by Johannes Hevelius. Photo by Torsten Bronger [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons.

This fall, PigPen Theatre Co. returns to Glencoe to tell a very different type of tale than the first time they stepped onto a WT stage. The Old Man and The Old Moon was a modern fable, attempting to explain a natural phenomenon (the waxing and waning of the moon) through an imaginative new mythology. This time, with The Hunter and The Bear, the group explores an equally revered style of classic storytelling: the ghost story.

Ghosts (or specters, phantoms, apparitions, spirits and spooks) are considered culturally universal, as every human civilization has shared a belief that those who have died continue to encounter or exert influence on the living in some way. Many references to ghosts survive from ancient cultures, including the Mesopotamians, the Egyptians, the Greeks and the Romans. Christianity in the Middle Ages created the concept of Purgatory where dead souls were condemned to pay penance for their sins. When a ghost appeared to the living, it might be one of these penitent souls from Purgatory, or possibly a demon, intent on temptation and torment.

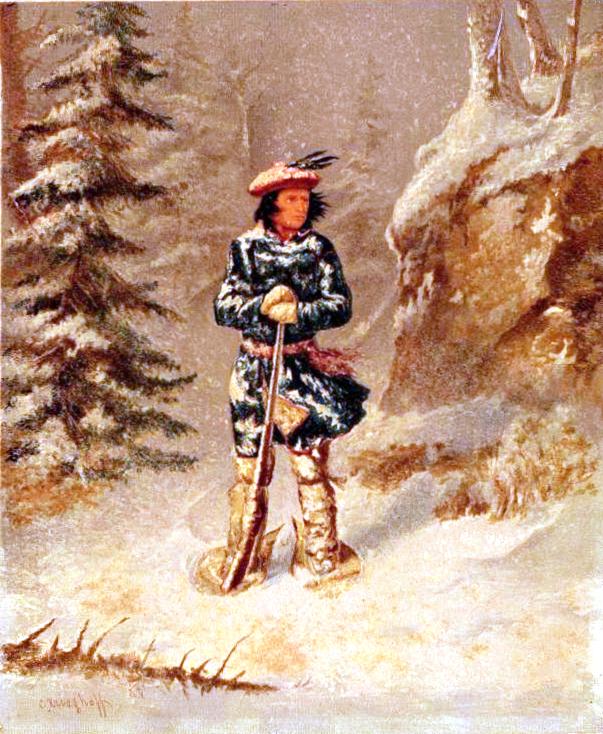

- Pictured: Iroquois Hunter in Doubt of Track by Cornelius Krieghoff (1868). [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons.

A belief in spirits was an accepted truth for much of human history, and classic authors had no need to justify the presence of ghosts in their stories as modern writers are now compelled to do. In the New Testament, Jesus has to convince the disciples who encounter him after the resurrection that he is not a ghost. Shakespeare often used ghosts in his works (Hamlet’s father, Julius Caesar, Banquo) and the characters that encounter them unquestioningly accept the validity of their existence. As the Scientific Revolution began to explain the natural world through means other than religion and mythology, however, human attitudes towards ghosts began to change, and so did their representation in art.

What we think of as the classic ghost story emerged during the Victorian era, experiencing a golden age from the 1830s until the First World War. The Romantics had revived interest in the wilder and darker parts of life, which gothic novelists like Mary Shelley took a step further, delving deeper into the macabre. But concise, structured ghost stories remained an oral tradition until the rise of periodicals in the 19th century. At that time, the process of publication had become easier than ever and publishing houses were in search of enthralling content. Ghost stories thrived in short story or serialized form, and took advantage of this revolution in the way that literature was consumed. Major contributors of classic Victorian era ghost stories include Edgar Allen Poe, Henry James, Washington Irving and even Charles Dickens with his famous A Christmas Carol. Since then, ghost stories have been adapted into all other types of media (plays, novels, films and television) and continue to thrive.

![Pictured: Scrooge's third visitor, from Charles Dickens: A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrations by John Leech. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843. First edition. [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.writerstheatre.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/Scrooges_third_visitor-John_Leech1843.jpg)

- Pictured: Scrooge’s third visitor, from Charles Dickens: A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrations by John Leech. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843. First edition. [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons.

While the form of The Hunter and The Bear is that of a ghost story, both hunters and bears have also been heavily featured in storytelling traditions. The role of hunter has always been a revered one in human tradition, given the importance of hunting during our hunter-gatherer days. The Ancient Greeks worshipped Artemis as the goddess of the hunt, and several hunters earned myths of their own, including Endymion (whom Keats wrote a poem about) and Orion (whose fame earned him a constellation in his name). New World cultures also celebrated the hunter. The Aztecs had a god of the hunt, Mixcoatl, as part of their pantheon, and the Iroquois had a legend of four hunters who chased a great bear, eventually pursuing the animal across the skies in the form of constellations.

Bears have been equally celebrated worldwide. The major way-finding constellations, Ursa Major (Latin for “great bear”) and Ursa Minor (“little bear”), are named after the predator, although in North America they’re more commonly known as the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper. Siberian, Scandinavian, Chinese and Korean cultures all regarded the bear as the spirit of their ancestors and adopted the creature as a symbolic image. Native Americans held the bear in similar esteem, associating the animals with healing and medicine. It wasn’t until later when agricultural civilizations came into conflict with bears that the animal began to be regarded as an adversary.

The Hunter and The Bear takes place in the Pacific Northwest and follows a company of loggers aiming to set up a business in the vast, unexplored woods. Tobias, the Hunter, occupies a respected place in the company for his ability to procure food. In this instance, the Bear is seen as an adversary—a feared beast who poses a threat to the success of their settlement. In crafting the story, just as they did with The Old Man and The Old Moon, PigPen Theatre Co. takes inspiration from a classic type of storytelling, drawing from the tradition of the ghost story and the many cultural legacies of hunters and bears to create a wholly original and modern musical folktale.

No comments yet.