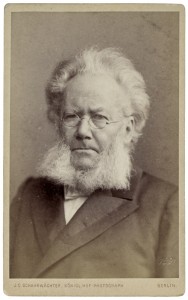

Henrik Ibsen is famously known as the Father of Modern Drama, and it is worth recognizing how literal an assessment that is.

Henrik Ibsen is famously known as the Father of Modern Drama, and it is worth recognizing how literal an assessment that is.

The Norwegian playwright was not merely one of a wave of new writers to experiment with dramatic form, nor did he make small improvements that were built upon by successors. Rather, Ibsen himself conceived of how the theatre should evolve, and, against great adversity, fulfilled his vision.

“The standing of the theater in the 1850s was at its lowest, in both Europe and the United States,” supplies Ibsen scholar Brian Johnston. “In Britain, for example, the last new play of any significance to appear until the arrival of A Doll’s House in London in 1889 was Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The School for Scandal (1777). During one of the most prolific periods of English-speaking literature, which saw the full flowering of the Romantic movement in poetry and the arts and the rise of the realistic novel as a major literary genre, not a single drama of major significance appeared. It was the period, in fiction, of Austen, the Brontës, Dickens, George Eliot, Hawthorne, Melville, James, Wharton; in poetry, of Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Tennyson, Browning, Whitman. No other period has been at once so rich in literature and so barren in drama.” Adding to the obstacles was the fact that Ibsen hailed from Norway, a country with almost no dramatic tradition of its own. Because Denmark had ruled Norway for the previous 500 years, most theatre was performed in Danish, by Danish companies.

Ibsen rose to prominence in large part because of his refusal to follow the rules of theatre at the time. His determination to forge his own style of drama coincided with a rising demand by the new intelligentsia for a serious “thinking” theatre, contrary to the frivolous entertainment on mainstream stages. Ibsen’s realist plays, such as A Doll’s House, Ghosts, and An Enemy of the People, were championed by this class of society upon their publication.

New theatres were formed in Berlin, Paris and London for the sole purpose of performing Ibsen’s plays, since no commercial mainstream theatre would consider it. “Within an astonishingly short time,” summarizes Johnston, “the theatre, through Ibsen, had shaken off its insignificance and disrepute to become a major, and highly controversial, force in modern culture.”

The playwright deviated from the theatrical norm in a variety of ways, most importantly, according to biographer Michael Mayer, by combining the three key innovations of “colloquial dialogue, objectivity, and tightness of plot.” His creation of settings, characters and narratives that were recognizable and relatable to his audiences was a monumental breakthrough. The plays, categorized as “Realism,” tapped into the intelligentsia’s discomfort with the hypocrisy between conventional moral values and the foundations and consequences of a post-Darwin, industrial-capitalist society. James Joyce summed up the groundswell of praise for Ibsen when he wrote: “It may be questioned whether any man has held so firm an empire over the thinking world in modern times.”

Ibsen’s major breakthrough in the English-speaking world came the year before he wrote Hedda Gabler. The June 1889 production of A Doll’s House at London’s Novelty Theatre, starring Janet Achurch as Nora, launched the playwright into public consciousness. London critics savaged the play in their reviews, but the show proved so popular the run had to be extended. The influential London actor-manager Harley Granville Barker (who would go on to stage and star in many of Bernard Shaw’s plays) remarked “The play was talked of and written about—mainly abusively, it is true— as no other play had been for years.”

Although A Doll’s House was new to the English-speaking public, the play was ten years old by the time it was performed in London in 1889. As a result, when Hedda Gabler opened at London’s Vaudeville Theatre in April 1891, only two years later, theatregoers were surprised at the direction Ibsen’s playwriting had evolved in what seemed like such a short time. In the intervening years, the playwright completed two plays similar in style to A Doll’s House (Ghosts in 1881 and An Enemy of the People in 1882). Ghosts, with a plot touching upon venereal disease and incestuous relationships, was widely banned. Ibsen then continued to delve into darker and more psychologically complex depictions. Reviews of his next plays, The Wild Duck (1884), Rosmersholm (1887), and The Lady from the Sea (1888) were mixed when first published, but acclaim for Ibsen and his work continued to mount. Hedda Gabler would continue this trend.

More on Hedda Gabler:

Articles | Videos | Production Details | Tickets

No comments yet.