Playwright Tom Stoppard has remarked that, in putting a play together, “what happens is you pull in all sorts of ideas which previously had been quite disconnected, which had been floating around in one’s mind for years…As usual I found that one has a play to write at the point where different threads, quite separate threads, begin to join up.” In Arcadia, four main threads join up over the course of the play and we will provide a little information about each of them in blog entries. All of these subjects —Classical and Romantic thought; “natural” gardens and the “picturesque”; Lord Byron and Lady Caroline Lamb; and chaos theory — intertwine their way through Arcadia, easily one of Stoppard’s most ambitious plays in what has been an incredibly ambitious writing career.

Lord Byron & Lady Caroline Lamb

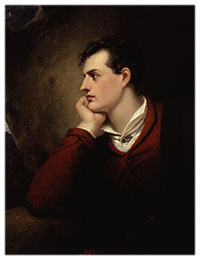

Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, who went by Lord Byron after inheriting a Barony at the age of ten, was one of the most famous poets of the Romantic era. His works, including the books Don Juan, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and the shorter poem “She Walks in Beauty,” remain landmarks of early 19th century literature and were wildly popular when published. Byron, however, was just as renowned for his lifestyle as he was for his writing. He accumulated enormous debts, exiled himself from Britain multiple times, had scores of affairs (with men as well as women), and died fighting in the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire. Despite a life lived so publicly, a handful of events in his life have remained difficult to definitively explain, exacerbated by the burning of his memoirs a month after his death.

Of particular importance to Arcadia is Byron’s initial self-imposed exile in 1809, the same year that he published his first book of poetry, Hours of Idleness, which he then followed with a scathing satirical attack to his critics, entitled English Bards and Scotch Reviewers. Byron wrote from Albania, “I will never live in England if I can avoid it. Why, must remain a secret.” After remaining abroad from 1809- 1811, Byron returned to England and published the first two cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, which were an instant success.

The fame of this success brought him into new social circles in London where he encountered Lady Caroline Lamb. Despite the fact that the Lady had been married for several years, the two soon began an affair that lasted until August of 1812. Byron biographer Leslie Marchand notes that “soon after their first acquaintance [Lamb] wrote dramatically in her diary: ‘That beautiful pale face is my fate.’” Ultimately, however, Lamb’s instability and indiscretion proved too much for Byron, as the publicity of their affair started having consequences for the ambitious poet. Byron began avoiding Lamb in June, and she resorted to showing up at his home in disguise and later threatening to desert her family or even kill herself for the poet. When Byron formally broke things off, Lamb’s husband took his devastated wife to Ireland for a year to prevent her from further destroying her reputation. Though their affair had ceased, Byron and Lamb would continue to write to each other, both publicly and privately, until Byron’s death in 1824, after which Lamb wrote to a friend, “I grew to love him better than virtue, Religion—all prospects here. He broke my heart, & still I love him….”

Hannah Jarvis and Bernard Nightingale, characters in the present-day scenes of Arcadia, are both scholars of 19th century Romanticism. Jarvis has recently published a book on Lady Caroline Lamb, and Nightingale is hoping to make a name for himself with a bold new theory about Lord Byron and what drove him into that first exile. Jarvis’s and Nightingale’s different approaches to scholarship also follow a Classical/Romantic split.

More on Arcadia:

Articles | Production Details | Tickets

Further Reading

Fleming, John. Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia. London: Continuum, 2008.

Marchand, Leslie. Byron: A Portrait. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Nadel, Ira. Tom Stoppard: A Life. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

No comments yet.