Playwright Tom Stoppard has remarked that, in putting a play together, “what happens is you pull in all sorts of ideas which previously had been quite disconnected, which had been floating around in one’s mind for years…As usual I found that one has a play to write at the point where different threads, quite separate threads, begin to join up.” In Arcadia, four main threads join up over the course of the play and we will provide a little information about each of them in blog entries. All of these subjects —Classical and Romantic thought; “natural” gardens and the “picturesque”; Lord Byron and Lady Caroline Lamb; and chaos theory — intertwine their way through Arcadia, easily one of Stoppard’s most ambitious plays in what has been an incredibly ambitious writing career.

Classical & Romantic

“Our urge to divide, counter balance and classify has never, perhaps, produced two denominations which work so suggestively over the infinite terrain of human expression. In speaking of Classical and Romantic literature, painting, music, sculpture, architecture or even landscape-gardening, we balance reason against imagination, logic against emotion, geometry against nature, formality against spontaneity, discretion against valor… But in so doing, we are drawing attention not so much to different aesthetic principles as to different responses to the world, to different tempers. ‘Romanticism’ is an idea which needed a classical mind to have it.” — Tom Stoppard

Stoppard deliberately used the conflict between Classicism and Romanticism as a means to frame the story of Arcadia. The Classical period, often referred to as Neo-Classical (or, alternatively, the Enlightenment) in order to distinguish it from the time of the Ancient Greeks and Romans, corresponds to the philosophy and art that emerged between the years 1660-1790. During this time, great thinkers such as John Locke, Jean- Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant, Adam Smith, Benjamin Franklin and the other founding fathers of the United States; and writers such as Jonathan Swift, Molière, John Dryden, Alexander Pope and Voltaire were building on the advances that had been made during the preceding Renaissance. Their writings were highly intelligent, witty and thoughtful, but always painstakingly rational in design and intention. Concurrently, the scientific community, including Isaac Newton and his companions in the Royal Society, made breakthrough after breakthrough, bringing order to the natural world with new rules and laws.

Stoppard deliberately used the conflict between Classicism and Romanticism as a means to frame the story of Arcadia. The Classical period, often referred to as Neo-Classical (or, alternatively, the Enlightenment) in order to distinguish it from the time of the Ancient Greeks and Romans, corresponds to the philosophy and art that emerged between the years 1660-1790. During this time, great thinkers such as John Locke, Jean- Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant, Adam Smith, Benjamin Franklin and the other founding fathers of the United States; and writers such as Jonathan Swift, Molière, John Dryden, Alexander Pope and Voltaire were building on the advances that had been made during the preceding Renaissance. Their writings were highly intelligent, witty and thoughtful, but always painstakingly rational in design and intention. Concurrently, the scientific community, including Isaac Newton and his companions in the Royal Society, made breakthrough after breakthrough, bringing order to the natural world with new rules and laws.

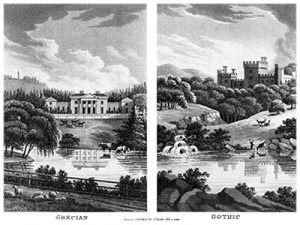

However, as the 19th century dawned, writers and philosophers began to rebel against the principled order and restraint of Neo-Classicism. Romantics placed renewed emphasis on emotion, rather than intellect, and advocated the importance of an individual’s free expression. Poetry, in particular, thrived during this period, with Coleridge, Blake, Wordsworth, Byron and Keats all making names for themselves. Other writers considered a part of this movement include Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, the Brontë sisters, Johann Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Alexandre Dumas, Alexander Pushkin and Edgar Allan Poe. In Arcadia, some of Stoppard’s characters at times embody a Classical inclination while others exhibit traits more in line with the Romantics. The clashes between these two temperaments is an overarching theme of the play that also plays out on a micro level in the evolution of garden architecture, poetry and physics.

More on Arcadia:

Articles | Production Details | Tickets

Further Reading

Fleming, John. Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia. London: Continuum, 2008.

Hunt, John Dixon and Peter Willis, ed. The Genius of the Place: The English Landscape Garden 1620-1820. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1988.

Marchand, Leslie. Byron: A Portrait. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Nadel, Ira. Tom Stoppard: A Life. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

No comments yet.