Playwright Tom Stoppard has remarked that, in putting a play together, “what happens is you pull in all sorts of ideas which previously had been quite disconnected, which had been floating around in one’s mind for years…As usual I found that one has a play to write at the point where different threads, quite separate threads, begin to join up.” In Arcadia, four main threads join up over the course of the play and we will provide a little information about each of them in blog entries. All of these subjects —Classical and Romantic thought; “natural” gardens and the “picturesque”; Lord Byron and Lady Caroline Lamb; and chaos theory — intertwine their way through Arcadia, easily one of Stoppard’s most ambitious plays in what has been an incredibly ambitious writing career.

Chaos Theory

While Stoppard put the focus of his play on the divide between Classical and Romantic thought, his original impetus for writing the play was a desire to explore the groundbreaking science of chaos theory. In his 1987 landmark exploration titled Chaos: Making a New Science, author James Gleick writes “[Some scientists] go so far as to say that 20th century science will be remembered for just three things: relativity, quantum mechanics and chaos. Like the first two revolutions, chaos cuts away at the tenets of Newton’s physics.” Isaac Newton’s groundbreaking laws were originally conceived to apply to an orderly world in which cause and effect are relatively easy to determine and predict, given enough information. However, complex systems such as the weather or population growth have proven to be infinitely complicated to accurately predict, despite their ability to be modeled with equations.

While Stoppard put the focus of his play on the divide between Classical and Romantic thought, his original impetus for writing the play was a desire to explore the groundbreaking science of chaos theory. In his 1987 landmark exploration titled Chaos: Making a New Science, author James Gleick writes “[Some scientists] go so far as to say that 20th century science will be remembered for just three things: relativity, quantum mechanics and chaos. Like the first two revolutions, chaos cuts away at the tenets of Newton’s physics.” Isaac Newton’s groundbreaking laws were originally conceived to apply to an orderly world in which cause and effect are relatively easy to determine and predict, given enough information. However, complex systems such as the weather or population growth have proven to be infinitely complicated to accurately predict, despite their ability to be modeled with equations.

Until the emergence of chaos theory, unpredictable outcomes in systems like these were attributed to randomness, but chaos offered a different conclusion. As Gleick explains, “tiny differences in input could quickly become overwhelming differences in output —a phenomenon given the name ‘sensitive dependence on initial conditions.’ In weather, for example, this translates into what is only half-jokingly known as the  Butterfly Effect —the notion that a butterfly stirring the air today in Peking can transform storm systems next month in New York. Only a new kind of science could begin to cross the great gulf between knowledge of what one thing does —one water molecule, one cell of heart tissue, one neuron —and what millions of them do.” While chaos was not defined until the 20th century, its rejection of classical Newtonian physics mirrors the rejection of Classical art by the Romantics in the 19th century.

Butterfly Effect —the notion that a butterfly stirring the air today in Peking can transform storm systems next month in New York. Only a new kind of science could begin to cross the great gulf between knowledge of what one thing does —one water molecule, one cell of heart tissue, one neuron —and what millions of them do.” While chaos was not defined until the 20th century, its rejection of classical Newtonian physics mirrors the rejection of Classical art by the Romantics in the 19th century.

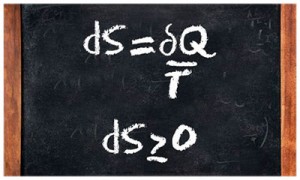

In Arcadia, the character of Thomasina Coverly, who is studying physics and mathematics in 1809, makes a prescient discovery of the second law of thermodynamics (“that heat can flow in only one direction, from hotter to colder,” which contradicts the backwards and forwards nature of Newton’s laws of motion) and is beginning to play with the principles of chaos theory more than a century before that science even had a name. In the present-day scenes, Valentine Coverly, a descendant of the family, is a mathematician who had been studying chaos theory at university and is examining it with regards to his family’s history of hunting grouse at their estate.

In Arcadia, the character of Thomasina Coverly, who is studying physics and mathematics in 1809, makes a prescient discovery of the second law of thermodynamics (“that heat can flow in only one direction, from hotter to colder,” which contradicts the backwards and forwards nature of Newton’s laws of motion) and is beginning to play with the principles of chaos theory more than a century before that science even had a name. In the present-day scenes, Valentine Coverly, a descendant of the family, is a mathematician who had been studying chaos theory at university and is examining it with regards to his family’s history of hunting grouse at their estate.

More on Arcadia:

Articles | Production Details | Tickets

Further Reading

Fleming, John. Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia. London: Continuum, 2008.

Gleick, James. Chaos: Making a New Science. New York: Penguin Books, 1987.

Nadel, Ira. Tom Stoppard: A Life. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

No comments yet.